Obsession

by Celeste PanRemembered chiefly for his time as editor of the avant-garde monthly publication The Dial in the 1920s when modernism was at its apogee, Scofield Thayer remained an elusive and essentially self-contradictory figure for literary and art historians. The American poet, publisher, philanthropist and aesthete has been described as a ‘Jekyll-and-Hyde paradox’, with his socialist leanings set against a bourgeois lifestyle, his unmistakable misogyny placed in blatant antithesis with a tenderly romanticist spirit. Perhaps no work has shed such an unique light on Thayer the private man than Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection, a selective catalogue as well as an illuminated biographical study on the collector and the artists alike.

The survey is of two parts. The first, by James Dempsey, documents the sometimes tempestuous, sometimes absurdly unremarkable 92 years within which Thayer lived. The second, compiled by Sabine Rewald, is a comprehensive account of both Thayer’s ‘art buying spree’ from 1921 to 1923 in continental Europe, and the personal and creative lives of Klimt, Schiele and Picasso.

Defying the generic convention of placing the catalogue proper after the introductory essays, the artworks from Thayer’s collection are integrated within the second essay itself, serving a role simultaneously illustrative and central. This symphony of images and text is paralleled by the abundance of photographs and reproductions in the section by Dempsey. It includes a striking studio portrait of Elaine Orr (by an ironic coincidence, of Troy, New York), Thayer’s wife from his only, brief marriage. The exquisite beauty of the composition and the model, alongside the shade of melancholy that clouds her eyes, provides a welcome counterpoint to the equally ephemeral brittleness with which many of the nudes are drawn.

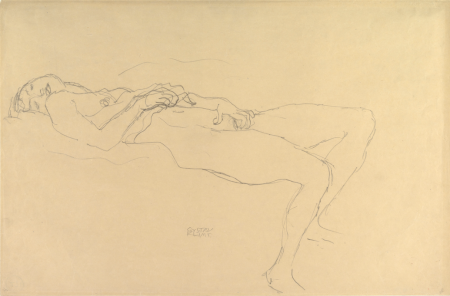

The most unusual feature of Thayer’s purchases is their relative unorthodoxy. Writing to his mother about the three artists in question, Thayer remarks ‘I do not care so much for their larger paintings’ whilst taking much delight in drawings and watercolours, which were ‘all astonishingly cheap and very charming indeed’. Indeed, the selection of nudes reveals a distinctly exclusive taste; none of Klimt’s richly dreamlike oils are to be found, nor is there any product of Picasso’s cubist period. The former’s drawings, in particular, possess a rawness and seeming carelessness often found in rough preliminary sketches; one image, Standing Nude, even includes faint lines of two extra legs growing out the model’s left hip, presumably from an earlier study on the verso of the sheet. The subjects, mostly women, are portrayed often during and after the bliss of self-pleasuring and lesbian lovemaking: their expression and posture, done in high realism, are endowed with a quality as fleeting and aqueous as Klimt’s soft, entangled pencil lines.

The works of Klimt’s protégé, Egon Schiele, exhibit a greater volatility of style and medium. The earlier crisp and minimalist drawings coexist with a more daringly grotesque presentation of the human body in the watercolours; while approaching the end of his life, he embarked on a more ornate Baroque mode, with firm and voluptuous lines only rarely associated with Schiele today. We do not need to elaborate upon the myriad of styles and subject matters adopted throughout Picasso’s career; the most intriguing segment thereof, included in the book, are perhaps the neoclassical drawings of bathers done in 1920. Deliberately evocative of figures on Greek vases, the women’s bodies are rendered with a curvaceousness of outline that recalls Schiele, while the emotive tone of the drawings comes closer to the serenity in Klimt that is both precarious and permanent. The interconnectedness across three disparate oeuvres draws the ‘showcase’ to a satisfying close.

An Epilogue serves to examine briefly other artists featured in Thayer’s collection, ranging from Pierre Bonnard to Georges Braque. If anything, the reader is left with a tingling curiosity for the remainder of the catalogue, especially those lying outside the post-Romantic tradition, such as those by Dürer and Rubens; however, their omission is largely understandable vis-à-vis their lesser relevance to the theme. Nevertheless, precisely due to their removed temporality, a cursory mention may have offered an equally, if not more, convincing attestation to ‘not only [Thayer’s] passion for, but also his visceral need of, the Sublime’.

Dempsey speaks of The Dial as ‘the crystallisations of Thayer’s energy, tastes, biases, and sheer will’; the same can very much be said in relation to his artistic acquisitions. It is more than a mere ‘obsession’, if we trust the OED’s definition of ‘an idea or thought that continually preoccupies or intrudes on a person’s mind’; rather, it is his mind—a mind that lives nowhere as vividly as it does here. Overall, this is an immensely intelligent and thoroughly enjoyable study of the life and art of one man, and also a generation.

Sabine Rewald and James Dempsey, Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art with Yale University Press, 132 pp, available in paperback.

Sabine Rewald and James Dempsey, Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art with Yale University Press, 132 pp, available in paperback.