Shunga : sex and pleasure in Japanese art at the British Museum

by Peter WebbIn the early seventies I was doing research for a book on erotic art, the first serious study of the subject. Information was very difficult to find. An early port of call was the British Museum, where I was informed that there was no work of that nature in the collection. Further inquiries resulted in a request for references from distinguished art historians. After providing these, I was granted contact with the Director who agreed to put me in touch with each department of the museum where such material might possibly be held. Thus I gained access one day to the marvellous collection of Japanese erotica in the Department of Oriental Antiquities, which, I was informed, could not possibly be exhibited to the public, and which had never been catalogued. After some negotiations, I was allowed to reproduce some examples in my book which was first published by Secker and Warburg as The Erotic Arts in 1975. It was therefore with some wry déjà vu that I visited the British Museum’s major Shunga exhibition where their collection is proudly displayed alongside examples from museums and private collections from around the world. Clearly a great deal has happened in forty years.

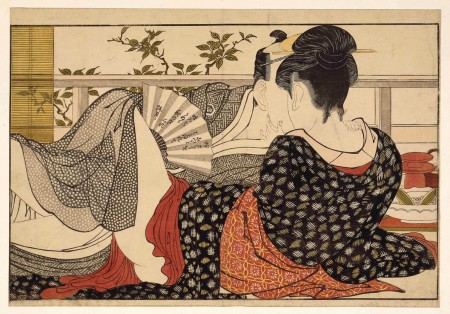

Shunga are explicit images of sexual enjoyment, usually in the form of albums of coloured engravings. They were an expected part of a Japanese artist’s work, created for entertainment and also for sexual instruction, and often given to brides on their wedding day. Humour is frequently present, as is a great deal of imagination, especially in the exaggeration of the size of the erect penises brandished by the men. Japanese artists do not use single-point perspective, and so are able to show the genitals in intercourse in ways that a Western artist would find impossible. Interest is added by the inclusion of everyday household furnishings and utensils, and it is not unusual to find a third person observing the proceedings. Complete nudity is rare. The universality of communal bathing in Japan tended to divest nudity of erotic implications, and beautiful garments in the latest fashion are shown as sexually stimulating. The prints were made exclusively by male artists, but were intended for the pleasure of women as well as men. The origins of this celebration of sexuality lie in Shinto, the Japanese religion which is based on fertility cults and which can still be seen in action in the regular religious processions featuring giant phalluses.

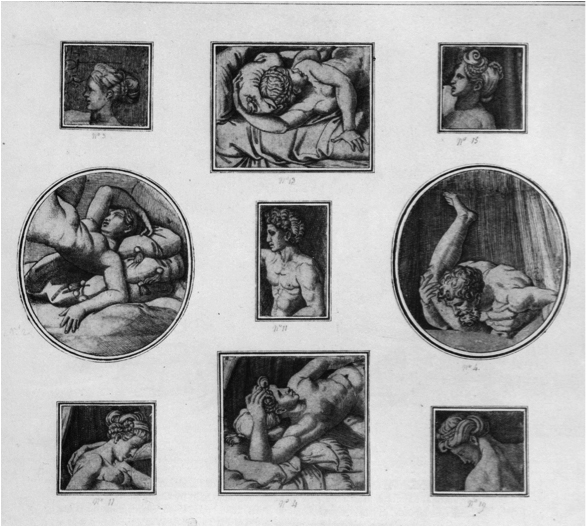

The exhibition includes a small number of erotic images from the West, starting with the remains of a set of prints made by Marcantonio Raimondi after drawings by Giulio Romano, censored (i.e. mutilated) by order of the Pope in the 1520s when Raimondi was briefly imprisoned. Thus the point is made immediately that artists in the East enjoyed a degree of freedom of expression denied their counterparts in the West. Thomas Rowlandson is shown to be a rare example of a Western artist able to produce erotic art with impunity, probably because of his friendship with the Prince Regent. Later in the exhibition, Beardsley, Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso are produced as evidence of Shunga’s influence abroad in a section that could have been usefully expanded. The first Japanese erotica to reach England were brought by Captain John Saris of the English East Company in 1613. They were immediately burnt by outraged Company officials. After Japan opened trade links with the West in 1859, such images found a ready market abroad with collectors such as George Witt who donated his collection of world-wide erotica to the British Museum in 1865. This became the Museum Secretum, hidden from the public gaze.

Japan had itself experienced periods of official censorship, but this had little effect until the early 20th century. Just as the West was beginning to explore sexuality, the Japanese authorities put a complete ban on Shunga as part of “cultural modernization “ which lasted until the late nineteen eighties. When visiting Tokyo in 1975, I was unable to find any erotic images in museums or commercial galleries. The involvement of Japanese institutions and scholars in the British Museum’s present exhibition shows that the historic admiration for Shunga has been fully restored.

The earliest Shunga in the exhibition date from the early 1600s and show gay and lesbian activities although mainly men with women. This diversity continued in the art of the great period, 1765 – 1850, when the leading artists, Utamaro, Kiyonaga, Hokusai and Hiroshige produced their finest work. All four are well represented here. The Poem of the Pillow of 1788 by Utamaro can lay claim to contain the finest of all Shunga. These twelve large colourful prints show a range of activities including lovers quarrelling and then making up, an ugly older man attempting to rape a young woman who defends herself, a sexual fantasy involving two female divers for abalone shellfish, one of whom watches in fascinated horror as the other is violated underwater by two river spirits, and a memorable non-explicit image of a couple embracing on the balcony of a teahouse. Here, tiny tempting glimpses of anatomy can be seen among the beautifully patterned clothing, a harmony of blacks and greys with touches of red. Utamaro is the best-known Shunga artist in the West. In the nineteenth century, the novelist and critic Edmond de Goncourt wrote of “the fiery passions of the copulations he depicted…those swooning women, their heads uptilted on the ground, their faces death-like, their eyes closed beneath painted eye-lids; that strength and power of delineation that make the drawing of a penis equal to that of a hand in the Louvre Museum attributed to Michelangelo.”

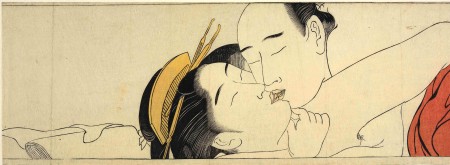

Kiyonaga’s Handscroll for the Sleeve of c.1785 is a long scroll, very narrow in height, designed to be slipped inside the hanging sleeve of a kimono, and depicting twelve close-up scenes of love-making. In this limited format, the artist has created a wonderful variety of poses and facial expressions. An album by Hokusai entitled Adonis Flower of c.1822-3 shows couples in an astonishing array of contorted positions including cunnilingus, with their exaggerated penises and vulvas depicted in loving detail. In each plate they are surrounded with a text detailing their conversation.

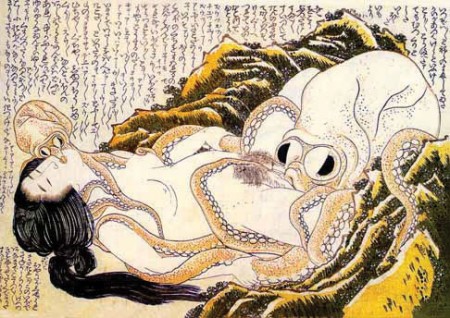

Hokusai’s most famous Shunga is The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife from an album of 1814. A giant octopus with terrifying eyes makes love to a woman among the rocks of the seabed, entwining her in his tentacles, while a smaller octopus kisses her mouth. From the text surrounding this startling fantasy, we learn that she is swooning with excitement. It is perhaps unique in Japanese erotic art in its power of design and sheer frightening drama. The importance of humour in Japanese erotic art can be seen in Hiroshige’s Deities Perform Music to Tempt the Sun Goddess of c.1847-52. The text on the print tells of the sun goddess Amaterasu who shut herself in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. The other deities performed lewd dances in front of the cave in a successful attempt to lure her out, as shown in Hiroshige’s bold image.

An information panel in the exhibition makes the claim that the finest Shunga are among the most powerful works of erotic art ever created. This is certainly borne out by this superb display.

Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art. 3 October 2013 to 5 January 2014 at the British Museum. Parental guidance advised for visitors under 16. Tickets £7.00, cloth-bound catalogue £40 (to be reviewed at a later date). Further information here.