Reclaiming Eroticism: a review of Defining Beauty at the British Museum

by James Cahill“About beauty they were never wrong, the ancient masters” – so W.H. Auden might have professed upon seeing Defining Beauty: the body in ancient Greek art, the British Museum’s most significant exhibition of Greek art in decades. It is a truism, after all – or an ingrained assumption – that Greek sculpture epitomises beauty in art, especially the classical Greek sculpture that emerged from ‘democratic’ Athens in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Since antiquity itself, this view has heavily shaped the way we think about art, and about beauty. And wandering through the low-lit chambers of the new Sainsbury exhibition wing at the British Museum, it is hard to deny the allure of the sculpted bodies on display. Lithe, torqued, tensed or rippling, they multiply into a pantheon of gods, athletes and heroes.

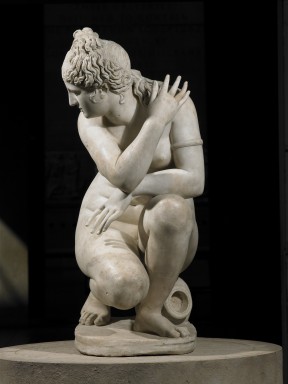

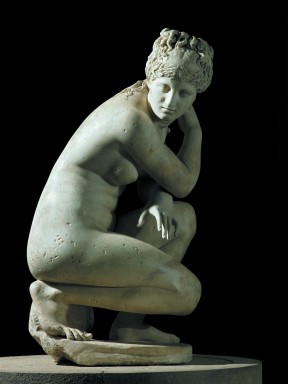

But is that allure a matter of beauty alone? In the first room of Defining Beauty, visitors encounter a marble representation of the goddess Aphrodite in a famous crouching pose, her back to the viewer (this particular sculpture, a Roman version of a well-known motif, is known as the Lely Venus – it was acquired by the portraitist Sir Peter Lely from the collection of Charles I following the king’s execution). What is striking, especially for the modern spectator, is not that she ‘defines beauty’ in any easy sense, but that the goddess is so earthily corporeal in the first place – tangibly and sexily embodied in spite of her stony substance. Her buttocks are round and full; her stomach folds in gentle undulations; her fingers extend over one shoulder in a gesture that might be a beckoning ‘come hither’, or a defensive admonition. Her entire furled stance is simultaneously guarded and inviting, protective and provocative. It counsels against totalising definitions. As we walk around the sculpture, the goddess’s visage comes into view: poised and imperturbable, it might equally be a fearsome glare or a look of serene introspection.

Gazing back at Aphrodite/Venus, one begins to sense that we have been blinkered by the presumed majesty of antique sculpture. Beautiful and majestic she may be, but these terms hardly capture her erotic charge and tantalising ambiguity. Could it be that ancient sculpture, in spite of the show’s title, reveals beauty’s very inexpressibility – its intersection with a range of other emotions and sensations? John Keats chased after this most elusive of ideals in the closing lines of his Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819): “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”. It is a soaring pronouncement, and Keats’s Romantic equation of aesthetic beauty with moral probity has enjoyed long currency. But it is also tellingly nebulous: what is beauty, what is truth? The questions have often been posed.

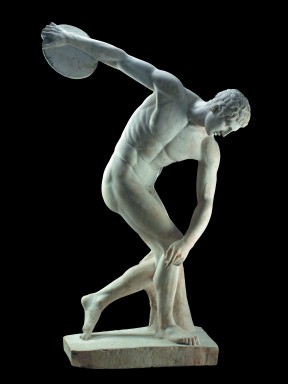

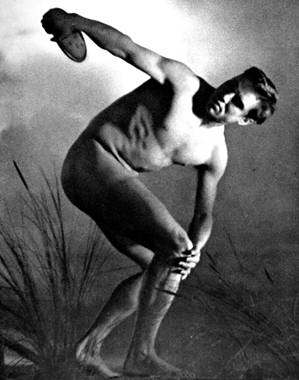

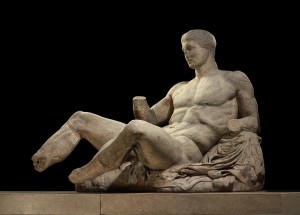

Keats had seen Greek sculpture first-hand: the Parthenon marbles arrived at the British Museum in 1816 courtesy of Lord Elgin. One of these appears close to the Lely Venus in the introductory room. It is the fragmentary figure of the river god Illisos from the Parthenon’s west pediment, a sprawled male body carved in marble, the torso swivelling to face us front-on. Designed by the legendary artist-cum- architect Pheidias, Illisos is one of trio of effigies presented as undisputed ‘greats’ of classical sculpture. Beside it we find the brawny nude male of Polykleitos’s Doryphoros / Spear Bearer – supposedly created as an illustration of the artist’s written treatise on harmonious proportion – and the Discobolus / Discus Thrower by Myron, familiar from many a school textbook on the Greeks and their virtuous athleticism. But in the case of these latter two, we are looking at reconstructions of the Greek masterworks rather than the real thing: the first is a bronze replica made in the 1920s by Munich sculptor Georg Römer, the second a marble ‘copy’ from the Roman era. Most of the legendary bronzes of ancient Greece only survive as Roman marble translations of this kind (hence the traditional view of Roman art as secondary, imitative, meretricious). Greek art is literally elusive: most of the bronze originals have long ago been melted down, and even a surviving marble figure such as the Ilissos is scarred and broken.

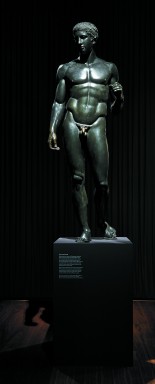

Once again, the exhibition succeeds (perhaps despite itself) in underlining the fugitive aspects of Greek sculpture – in this instance, the sheer absence of original works. Even as we are presented with the canonical pinnacles of Greek art, we are reminded of the canon’s irretrievability. And as the Lely Venus shows, that quality of elusiveness often extends to the very attitude of a figure. Even when we know everything about its original appearance and function (and this is rare), there is frequently a coyness about the Greco-Roman body, residing above all in its averted gaze. It is at strange odds with the openness of its nudity. Defining Beauty features a statue that makes the point well – a Hellenistic (i.e. first or second century BC) Greek bronze of a young man recovered from the sea near Croatia in 1996, on show for the first time in the UK. It is one of the rare examples of a Greek bronze, saved from destruction by virtue of sinking in a shipwreck. Known as the Croatian Apoxyomenos, the naked athlete glances down (through now-empty eye sockets that would once have been filled with glass, stone or copper) as he scrapes sweat from his leg with a missing strigil; and in this ‘frozen moment’ we glimpse some of the same profound ambiguities as in the Lely Venus. The downward-cast gaze speaks of self-containment, obliviousness, even a mental hiatus; and through this seemingly casual gesture – a refusal to fix the viewer’s gaze – the sculpture thus asserts its own autonomy from fixed meaning. It slides from our interpretative grasp.

Much has been said about the realism of classical Greek sculpture, but this bronze athlete – like so many others – veers between real and hyperreal registers. However honed and muscular, bodies never look this superhuman in real life. On the other hand, there is no getting away from the palpable, physical humanity of the figure. The nipples and lips are inlaid with pinkish copper that mimics flushed skin. The dark gleaming patina is not simply the ‘lustre of bronze’ – it is also redolent of a sweat-streaked body in the sunlight: the athlete has the glow of a living being rather than the empty sheen of an effigy. And so there is a push-pull effect, not only between idealism and realism, but between bronze medium and fleshly subject. Neither quite wins out. (In a strained attempt to rationalise the tension between realism and idealism in classical statuary, Goethe conceived of two distinct levels of naturalism – “common” nature or “nature in the raw” versus “noble” nature). The ambivalence is only heightened by the athlete’s contrapposto stance – his weight resting on one leg and his body arcing sinuously, in a pose that suggests arrested movement, something between a walk and a halt. Again, it is the figure’s ‘inbetweenness’ that shines through. He is poised between the ideal and the real, hero and man, glossy exteriority and psychological interiority. It is this very ambivalence that typifies much ancient Greek art, in its delicate mediation of eroticism and beauty.

Despite the exhibition’s title, what emerges continually from the display is a sense of the ambiguous – perhaps indefinable – dynamic between physical beauty and erotic power. The presentation of the objects in Defining Beauty, overseen by senior curator Ian Jenkins, is a feat of scholarly selection and stylish design; there is a wealth of artefacts on view – much more than the scope of this review encompasses – and a mass of contextual information to match. And yet the exhibition falls back too readily on that age-old assumption, voiced by Keats, that Greek figurative art embodies ‘beauty’ in the sense of a universal and soberly intellectual truth – as if a lofty abstract ideal could be set forth in plain figurative guise. In apparent endorsement of the notion, one gallery is called “Giving form to thought”; and along the same lines, Jenkins writes in the catalogue that “While breathing life into stone or bronze, a sculptor could transcend nature to give form to thought in works of timeless beauty”. The concept of beauty was doubtlessly bound up, in ancient Greece, with ethical values, but was it the sole or dominant property of art? What we are inclined to forget is that statues very regularly had a narrative identity – they portrayed figures with stories, fictional lives. Inherent in many of those fictions were love and desire. References to sexuality in the catalogue are all too brief and concessionary; they tend to home in on overt moments of “unfettered lust” in vase paintings or the allegorical personae of Eros and Aphrodite, rather than the more diffuse eroticism pervading classical statuary. It would seem that the Romantic gloss given by Keats and others to the Greek ideal of moral and physical beauty (kalokagathia) has hardly dimmed in three centuries.

Perhaps Plato is to blame for all this, for arguably it is his definition of ‘Beauty’ that we continue to hanker after – beauty as an ideal Form so perfect and pure that it cannot be seen, but only channelled into inferior substitutes in nature. (For this reason, Plato was disapproving of art altogether, seeing it as a degraded copy of a copy). A decidedly Platonic denial of the body’s erotic (often homoerotic) valency is evident at various moments in the exhibition, and this despite the curators’ admission in one wall text that “Sculptors and painters delighted in representing erotic desire”. Implausibly, the erect penis of a tiny bronze man from the eight century BC, showing the warrior Ajax turning his dagger on himself, is rationalised as “the sculptor’s device for conveying the extreme trauma of the moment”.

How likely is this? There are few other situations, in either art or life, where we would readily interpret arousal as a token of anxiety. More viable, surely, is the idea that the little figurine’s conflation of sex and death is meant to seem strange – the petit mort of the orgasm meeting the real thing. If anything, the oversize erect member, pointing back at Ajax like the needle-like sword he holds, serves to remind us of what landed him in trouble in the first place. After being denied the armour of Achilles in a contest, Ajax made a botched attempt to murder his fellow Greek leaders. When the plan failed (he was tricked by the goddess Athene into slaughtering livestock rather than men) he was driven to commit suicide in shame. He was the victim, therefore, of what we might call his own ‘dickishness’ – his heroic swagger and amour propre. Even in his final act of self-martyrdom we find an allusion to the bullish masculinity that defined him, and destroyed him.

So much for erections: it is the smallness of the men’s genitals that is remarked on elsewhere, interpreted as reassuring evidence of sculptors curtailing the eroticism of their creations. The genitals of a Roman Victorious Athlete of the first century AD are, for instance, described as “understated to reduce the erotic charge and heighten the moral imperative” of the statue. But two factors run against this interpretation. Firstly, the penis of this figure has been lopped off altogether, either by accident or through an act of emasculating vandalism: the genitals have been dismantled rather than consciously understated, making it hard to impute a moralising motive – at any rate to this particular sculptor. (And even where the genitals of male nudes do appear intact yet small, we should still credit the Greeks with being happier to ‘bare all’ than their censorious Christian restorers, who often appended fig leafs to the genital regions). More significantly, the “erotic charge” of the Victorious Athlete clearly permeates the entire body rather than being concentrated in the genitals; the statement quoted above almost implies that only the sight of ample genitals could elicit desire in the viewer. This is made clear by the positioning of the Victorious Athlete close to a similarly-sized statue of the young Bacchus; we are invited to interpret the two figures, athlete and god, in relation to each other. Bacchus is a lithe and lilting youth; his long hair is girdled with grapes; and his shoulders are draped in a cloth that does nothing to hide his long naked waist and thighs. He holds a cup of wine and reaches down to caress a strange childlike creature, Ampelus, who emerges from a tree, decked in clumps of grapes (a personification of the vine). The portrayal is unambiguously sensuous, and throws light on the eroticism inherent in the first statue. Looking back at the body of the Victorious Athlete, we realise that he is just as smooth and limber as Bacchus, if less coquettish: they might be the same youth playing different roles, burlesque and noble.

In this juxtaposition, and indeed everywhere in the exhibition, we are confronted by the fact that the Greek nude – however grand or idealised – emanates an eroticism that is in no way at odds with its moralising beauty. A krater or mixing bowl shows a naked youth with the tagline “Leagros is beautiful”. Tellingly, the word for ‘beautiful’, kalos, might alternately be translated as ‘comely’, ‘handsome’, or ‘sexy’. And when we remember the context in which this image would have been seen – the louche, homosocial event of the symposium or all-male drinking party – it is hard to imagine that the painter of the cup intended to compliment Leagros in terms that were strictly aesthetic and primly moralising.

In a gallery that contains diverse painted replicas of archaic statues, there is a projected quotation from the Greek lyric poet Bacchylides which reminds us of the subject at the heart of ancient sculpture – the body as a living, and thus sexual, entity: “He showed his lovely [thaumaston] body to the great ring of the watching Greeks”. High-minded as ancient athletics contest may have been, they were also erotic pageants. Walking through Defining Beauty, it seems increasingly strange to think that a naked body – with all its obvious erotic possibility and puissance – could ever be wholly abstracted and purified by art. As Matthew Bell remarks in the catalogue, “Greek sculpture was a product of a public display of the naked body” – and this ought to discourage us from distinguishing too cleanly between art and life.

Indeed, how can a body not appeal to our sense of the erotic, even when that sense is complicated or affronted by the sight of something taboo, monstrous or grotesque? The exhibition contains various examples of bodies that seem to eschew any conventional definition of beauty, sometimes delving into bizarre fantasy, and yet they retain a crucial sense of the visceral. Some bodies are unlovely yet oddly compelling – inhabiting a kind of ‘low classical’ genre, perhaps, to counter the ‘high classical’ aesthetic that continues to colour our view of ancient Greece as a realm of “sweetness and light” (in the ardent words of Matthew Arnold). What are we to make of a colossal head of Herakles which presents the hero as thuggish and literally ‘block-headed’, his hair and beard a thicket of tight macaroni-like scrolls? There is little of either sweetness or light about him. The jauntier aspects of the body emerge, meanwhile, from many of the ancient Greek vases on display; the recurring motif of the lusty satyr reminds us that humanity is only ever so good or so wise – apt to tilt at any moment towards baser instincts. On a more otherworldly plane, there is the stone sphinx (probably a table support in second-century AD Rome) whose heavy-set, square stature belies its slippery identity – it is neither woman nor bird nor cat, but a fusion of all three. Time and again, we find that the idealised body had its ‘other’ – whether brutish, bawdy, or surreal.

In one extraordinary work, these two strands – seductive beauty and jarring otherness – dovetail in the image of a body that powerfully asserts the indefinability of the erotic. The Roman marble Sleeping Hermaphroditus represents a nymph-like figure lying front-down on a mattress, buttocks in central view, with the bed sheets winding around one leg that kicks lazily upwards. It is a portrayal of the mythological character Hermaphroditus, born a boy and transformed into an androgyne after the nymph Salmacis clung to him longingly in a woodland pool, willing their bodies to meld. As we circumvent the statue and view it from the other side, its male genitals are revealed, tucked snugly yet unmistakeably between its legs.

Boy and girl, nobility and nubility – all are collapsed together in this figure, which shows its lovely body (or bodies) – in Bacchylides’s words – for all who watch. The Victorian poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, writing about a similar Hermaphroditus now in the Louvre, was moved to typically lubricious praise of the image: “sex to sweet sex with lips and limbs is wed.” The dimpled mattress and rumpled sheets were added in the mid-eighteenth century by the sculptor Andrea Bergondi, but they only compound the multiple subtle effects of the naked sleeper. Stirring in slumber, Hermaphroditus has the quality of sealed interiority that we find in other statues, but more obviously so. Indeed, the work can be seen as dramatising the ‘erotics of spectatorship’: the nearly-awake Hermaphroditus is the passive receptacle of the viewer’s (potentially eroticizing) gaze, but appears also to enjoy his/her own erotic agency. That is, the artwork elicits desire by dint of seeming to harbour desire itself. The listless kick of one leg seems, in contrast to the passive prostate body, an active – almost flirtatious – expression of sexuality, the sign of something stirring. And so the uncertain gender of Hermaphroditus is mirrored by the languorous pose, suspended between provocative passivity and a more active expression of desire.

There is a danger, of course, in imputing too much erotic power to a statue, a madness in willing bronze or marble to be sensate and sexual. The myth of Pygmalion, as told by Ovid, famously parodies the sculptor who falls helplessly in love with his own ivory creation. And the stories surrounding Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos, of which a Roman marble version is on display, also point to the ruinous erotic power of that particular image. Pseudo-Lucian and Pliny tell the lurid story of an aristocratic youth from Knidos stealing into the Temple of Aphrodite in order to fondle, kiss, and finally besmirch Praxiteles’s artwork with an incriminating stain on the thigh. He meets a grim end, throwing himself upon the rocks in shame when his crime is perceived. The story might be taken as a warning against our regarding a divine statue in such a basely sexual way, but the fact remains that such works were seen to harbour erotic power, and that such power might have been intrinsic to what we nowadays sedately call their ‘beauty’.

There are many other aspects of ancient art – its funerary or commemorative functions, its use on the drinking vessels in symposia – that Defining Beauty expertly traces, and which this review had barely touched upon (concerned as it is with the eroticism of the body in sculpture). But it is hard to deny that Greece’s greatest bequest to the history of art has been the naturalistic nude figure. And while it would be wrong to cast ancient art as flagrantly and blithely eroticizing (the female body remained clothed until the mid fourth century, before which it was portrayed through a film of diaphanous drapery), we are at risk, still, of approaching the Greek body from too demure a perspective, one that veers ultimately towards the prudish. As long ago as 1880, in his essay The Beginnings of Greek Sculpture, Walter Pater argued that we should reclaim the sensuous and bodily nature of Greek sculpture, ceasing to see it merely in formal and intellectual terms. And yet, to invoke the dualism famously expounded by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) between Apollonian classicism (bright, finite and pure) and the Dionysian realm of the senses, we have surely continued to drift too far towards the former.

To return to Myron’s Discobolos / Discus Thrower, there is undeniably something serious, stolid and rather sexless about the Roman marble version. Little wonder that it appealed, in all its restrained dignity, to filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, who recreated the pose in the opening moments of her epic piece of Nazi propaganda Olympia (1938), a celebration of the Munich Olympics; Hitler also owned a marble version of the work. But medium may well play a part in this dour effect: cast bronze (the materialof Myron’s lost original) was a lighter, suppler and more versatile than marble (transferred from a modelled clay prototype, rather than laboriously hacked and chiselled and planed out of a stone block). As the Croatian Apoxyonemos showed, bronze is more apt than painted stone for reproducing the burnished surface of an athlete’s skin. And so it is tempting to imagine that the lost bronze by Myron (who was, after all, famed for his realist style) – flashing in the sunlight rather than subdued by the sepulchral indoors – exuded a sensuality to rival that of Leagros, the beautiful youth depicted on the wine cup.

The fact that athletics in ancient Greece took place in the nude and outside is not simply a testament to ‘Grecian nobility’; it surely tells us that these contests represented an erotic spectacle as much as a competitive event and civic ritual. That idea of a competitive event with an unavoidable erotic undercurrent furnishes a revealing way of looking at the celebrated pair of sculpted bodies with which the exhibition closes. The first is the Belvedere Torso, a monumental marble fragment (probably carved in the first century BC) of a heroic figure, whose head and limbs have been shorn off. Michelangelo idolised this statue and refused to restore it out of respect for its beauty as ruin. Then there is a giant reclining male from the Parthenon, possibly Dionysus. Dionysus faces the Belvedere Torso, each seeming to square up to – or eye up – the other naked male as if from opposite ends of the gymnasium or palaestra.

Each statue has been irrevocably excised from its original context, and in the case of the Torso we have no idea what this context might even have been. But by setting the two works in this charged, almost competitive dialogue, the show invites us to pay closer intention to the ways in which masculinity was embodied – and problematised. Each exudes a brutal power – larger than life, and clad in muscle and sinew. It is easy to see what moved the Enlightenment art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann to such excessive and eroticized praise of the Torso: “What a conception we gather from those thighs, whose solidity clearly shows that the hero has never flinched, and never been forced to bend!” (Bell, writing in the catalogue, is content to interpret such ardour as a Neoplatonic form of “sexual desire stripped of physicality and sublimated into something pure and philosophical”; yet this is hard to reconcile with the voluptuous physicality of what Winckelmann actually writes).

But each also expresses vulnerability. In the case of Dionysus it is subtle – he lies a just little too torpidly and passively to seem altogether virtuous (as would be appropriate of the louche and unruly Dionysus). In the case of the Torso, on the other hand, the vulnerability is a function of the damage suffered by the statue: the heroic body has been assailed and maimed by time. Tellingly, the Torso has been interpreted variously as the demigod Hercules – a paragon of heroic power – and as Marsyas, the satyr who was mercilessly flayed by Apollo. Once again, heroism carries with it a sense of its opposites, whether luxuriance, enervation or victimhood. We are asked to see the body as something real and contradictory and fragile, rather than as a symbol with one clear meaning.

What Defining Beauty continually reveals is that the blurred boundaries between artistic and actual bodies, between idealism and realism, and between beauty and eroticism, were never more pointedly probed than by antique sculpture. Some of the ambiguities of ancient sculpture are admittedly a consequence of time – most Greek art has been irretrievably lost, and much of that which endures is hard to place or identity. But the bodies in Defining Beauty hint also at the fact that meaning many never have been as fixed as we suppose. What if we look at the body in the nuanced way that the surviving sculptures, seen on their own terms, seem to demand? That is, as bodies with all the ambivalence of a bodies, and not simply in clinical aesthetic terms of design and proportion, or as physicalised expressions of abstract virtue?

Ironically, the works in Defining Beauty deny the possibility of some timeless and essential quality of beauty. Beauty, eroticism, ugliness or any other such quality are not encapsulated within artworks like flies in aspic, but are engendered in the subjective moment of viewing. This accounts for the fundamental indefinability that permeates antique sculpture. It seems so easy to typecast – as beautiful, heroic, sacred or realistic – but is often radically multivalent. The body, as refracted through Greek art, doesn’t simplify life into a finite image of beauty, but rather mirrors reality’s complexities. It can be seen – and seen again – in manifold ways.

Defining beauty: the body in ancient Greek art; 26 March – 05 July 2015, Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery, The British Museum £16.50, Members/under 16s free