A Flatbush Upbringing

by Bruce AbrahamsAged 13, I arrived in the common room of my new boarding school to be greeted by the supervising senior boy with ‘So you’re the new boy, Abrahams, bit of a wog are you?’ I had no idea what he meant so merely smiled and accepted. I was ‘wog’ for the rest of my time (enjoyably spent) at the school, even to the masters. This was an era when Britain’s leading maker of sewing cotton had a colour labelled ‘nigger brown’.

In due course I learned that the term ‘wog’ applied to people of Middle Eastern origin. Much later I questioned the family fable of Welsh ancestry. My father was born to a refugee family of Russian Jews. My mother was however a proper Cockney goy, my father converted to Christianity and I grew up thoroughly C of E. The reason for this as Dad in old age confessed was ‘I didn’t want you to grow up being persecuted like I was.’ Challenged as to why he didn’t change the family name he said; ‘I couldn’t bring myself to do it.’

My Jewish friends love this story. It speaks not just to the strength of Jewish identity but of the human proclivity (whatever the genetic or cultural start point) to preserve a coherent narrative of origin and affiliation. This is not always productive. It can create distance and suspicion between groups of differing communities. Jews are not the only people to experience the consequences of perceived ‘otherness’ and dissociation from the dominant group norm.

Even so, Jews have a unique claim to our attention in the context of prejudice and persecution that goes beyond mere discrimination. Many horrors for many peoples resulted from the pursuit of various dreams of Empire across time and geography but few were so focused, perennial and ruthless as that inflicted on the Jewish.

This demographic (to use current parlance) has attained in the West, at least, an outstanding level of intellectual achievement and in all but extreme circles, generally unremarked acceptance. Although as the Labour Party’s recent difficulties show, old prejudices lurk very close to the surface in British society. At the same time large numbers of its membership have, like my father, opted out of the club, changed names and (like many Catholics) become non-practising.

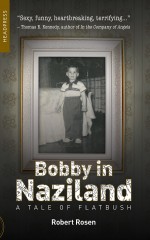

Robert Rosen’s fluent and vivid memoire is a very specific narrative about a New York Jewish upbringing. He places it in both the cultural milieu of its time (late fifties, early sixties) and the Holocaust as glimpsed by him and experienced or remembered by others of his friends and family. On the way, we take in John Lennon’s murder and the trolling of the author for his book The Final Days of John Lennon.

To read the book is like being read to. The style and voice – matter-of-fact, witty – deliver his portrait of life growing up in Flatbush with great charm. He reminded me of Philip Roth in Portnoy’s Complaint or J D Salinger and Catcher in the Rye. But, like a small cloud hanging on the horizon of the reminiscence, there is a darkness that is the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. It overshadows Rosen in a shockingly sudden way and now lingers threateningly in Trump’s America as a postscript. Trump’s support for Israel should not delude anyone that his followers like Jews.

I have only experienced the most peripheral anti-Semitism. If asked about being Jewish I qualify my denial by declaring my father’s ancestry. It seems cowardly and disrespectful not to. Rosen’s book is a powerful reminder that Jews could be seen as symbolising all persecuted communities. The Holocaust also reminds us why Israel (whatever one thinks of its current leadership and policies toward Arabs) is so important to Jews.

Robert Rosen, Bobby in Naziland – A Tale of Flatbush, Headpress.

Robert Rosen, Bobby in Naziland – A Tale of Flatbush, Headpress.